by Natasa Stasinou

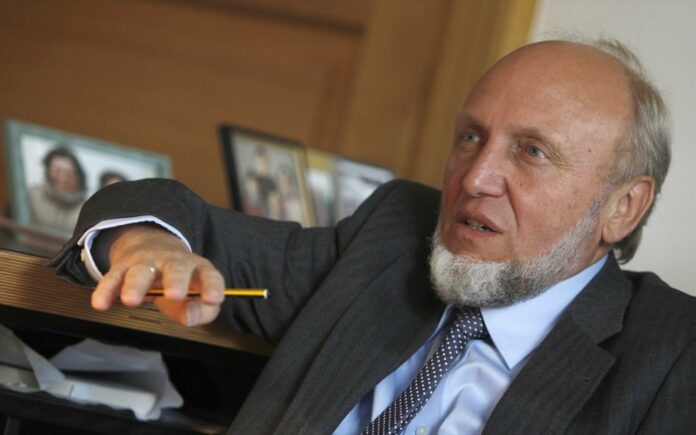

Influential German economist Hans-Werner Sinn continues to maintain that Greece’s temporary exit from the euro zone, in tandem with a debt “haircut”, is unavoidable for the country, if it wants to restore its competitiveness.

In an interview with “N”, Sinn, who headed the Institute for Economic Research (Ifo) and also serves on the German economy ministry’s advisory council, details the radical option: converting all values within the country from euros to drachmas, and with a ratio of 1:1.

More ominously, he warns that the most recent agreement between Greece and its creditors will lead to a new “debt spiral”, while at the same time referring to “mistakes” by the German side and Greek politicians.

Finally, he reiterates that a European Union without political integration has no future.

How do you evaluate the latest agreement reached between Greece and its European creditors in the Eurogroup?

While these are far reaching concessions for Greece, I see nothing that would help Greece regain competitiveness. This is the foundation for new debt spirals in the future.

You have consistently argued in favor of a Grexit, followed by a debt writedown, as the only viable solution. However Greek economists warn that in this case we will have a deep bank deposits “haircut”, asset devaluation of 50%, minimum inflation of 10%, even harsher austerity, great difficulty in importing food, medicine, fuel, social upheaval. All these would come after eight years of recession. Greece has already been through a painful experiment. Can it go through yet another one?

Returning to the drachma and giving Greece a haircut is like pushing the reset button. It will quickly help Greece recover due to the devaluation of the drachma that would take place immediately. All internal contracts would be converted to drachma over night including all accounts, all savings, all credit obligations, all wages, all prices, all rental contracts. The numbers in all these contracts would remain the same, but the euro signs would be exchanged for drachma signs. Note that this would not be an EU exit and that I have always argued that Greece should have the right to return to the euro after a number of years when the exchange rate has found its new equilibrium. Greece could even legally keep a non-voting seat in the ECB council.

So the numbers in all these contracts would remain the same, but the euro signs would be exchanged for drachma signs. What would be the real devaluation of wages, savings, assets though?

That would be determined by the markets. No one knows, my guess would be 50% initially, and perhaps a recovery to 30% after a few years. But that would not be a problem, but a desired effect, as Greece would return to the landscape of potential investment locations.

How would you convert the bank notes?

Ideally, all bank notes would also have to be converted, but as this is technically difficult if not impossible, one might also leave the euro bank notes with the people, which would be a huge conversion gain for Greece.The euro bank notes could be used for cash transactions before drachma bank notes are printed, and thereafter they could stay in the country as a parallel currency or be used for purchases abroad. But only drachma would be legal tender.

And what about foreign debt and the cost of imports?

In my plan, foreign debt of the government, the banks, the central bank, firms and households would also be converted to drachma, so that the devaluation loss is with the foreign creditors. The EU would help Greece by subsidizing sensitive imports like medicine that cannot be produced in Greece. The advantage of this solution is that people’s consumption shifts from imports, which become more expensive as the drachma devalues, to domestic products. Agriculture, food processing, textile industry and just about every production sector would recover. Even the traditional cotton industry might return. More tourists would come as Greece becomes cheaper. Greek flight capital would come back and trigger a real estate boom which will generate more jobs in the construction industry.

You argue that foreign debt would also be converted to drachma. However experts say that this is legally not possible. What makes you think that foreign creditors would accept something like that, that as you note shifts the devaluation burden to them?

The experts are right when it comes to privately held public debt issued by the Greek state, because that debt was converted to British law in 2012. But private debt is today of only minor importance. Most of the debt is with public institutions, the ECB in particular, and of course any kind of hair cut about that debt can be negotiated. Mind in this context that the Greek economy has a net foreign debt position of 223 billion euros while its debt with public institutions including the eurosystem is 339 billion euros, indicating that about one third of public credit the Greek economy received was converted into foreign investment by Greeks who fled with the money to other countries.

How much time would a recovery take?

The recovery will come within one, two years. That is the experience ifo documented in an extensive study based on 71 countries that went through a currency crisis after the war and devalued. (https://www.cesifo-group.de/portal/pls/portal/!PORTAL.wwpob_page.show?_docname=1214631.PDF) The rate of unemployment will rapidly decline, in particular among the young. Except for imports which should become more expensive to induce people to buy Greek products, the inflation fear is unwarranted as Greece is currently overvalued. It would need to be come cheaper, but becoming cheaper through a real devaluation inside the euro is exactly the mess Greece currently experiences.

You have suggested that Germany would also be better off, without the euro. However it is believed that is one of the main beneficiaries of the common currency. Is this not true?

The euro was no advantage for Europe, not even for Germany. Germany’s GDP per capita in 1995, which is the year of the Madrid summit when the euro was ultimately announced, was second after Luxembourg among the countries now in the euro. Today Germany holds the seventh rank. Germany’s net foreign wealth built up via export surplusses consists largely of Target claims of the Bundesbank on the euro system that result from the fact that countries like Greece have redeemed their foreign debt and bought foreign goods and assets by activating the local electronic and physical printing press. According to the balance sheet of the Greek Central Bank, the Greek economy has drawn overdraft credit from the eurosystem of 115 billion euros, two thirds of its GDP, for these purposes. Nevertheless I would not advocate Germany abandoning the euro, as the euro is also an important European integration project.

You have been very critical of the way the German government responded to the debt crisis. What could be done differently?

I would have supported Papandreou in 2011 and Varoufakis in 2015 who wanted to exit the euro.

Papandreou, however, has never supported (at least not in public) the idea of Greece exiting the Eurozone. And Varoufakis recently stated that threatening Europeans with Grexit was just a negotiation tactic.

Varoufakis is a good economist and intelligent person. He must have known that the introduction of a parallel currency which he admitted to have prepared for half a year in an interview with New Statesman (http://www.newstatesman.com/world-affairs/2015/07/yanis-varoufakis-full-transcript-our-battle-save-greece) would automatically have lead to the full conversion into the drachma. After the referendum he also wanted to capture the Greek Central Bank, as he said in the interview, but Tsipras, who knew about the secret negotiations according to Varoufakis, then said no, and Varoufakis quit. Capturing the Greek central bank by the government would have meant the immediate exit. And concerning Papandreou, please read the book “Inside the Euro Crisis” by Simeon Djankow, who was Bulgarian Finance Minister and member of the Ecofin Council. He says Papandreou secretly prepared the exit for the time after a potentially failed referendum. Read also my book The Euro Trap which appeared in 2014 with Oxford University Press concerning similar ideas by Berlusconi. I also asked Papandreou early this year about that in Munich and he agreed in public that an exit in 2011 after a failed referendum would have been better for Greece.

The German government and Bundesbank strongly oppose ECB’s policy and especially the quantitative easing program. Why is that? Hasn’t the German economy benefited from a weak euro and the low borrowing cost in the debt markets?

The euro is way to cheap for Germany. Germany needs a strong revaluation to improve its terms of trade to reduce its useless trade surplus and raise the living standard of consumers. Germany cannot benefit from low interest rates, as the German eonomy in its entirety it is a net lender to the world, in fact the second largest after Japan. Low interest rates benefit borrowers and hurt lenders.

In your book “The Euro Trap” you warn that the Eurozone is doomed to “decade of crisis”. Is there a future for the monetary union without true economic and political integration?

No. It makes no sense to have a common currency and separate armies, for example. We got the sequencing wrong.

It is widely believed that the prospect of a Brexit is the biggest threat to the future of the European Union. What would it mean for Europe if the British chose to leave?

Mind that Britain would exit the EU, not the euro. It would undermine the European idea, hurt Britain and hurt continental consumers.